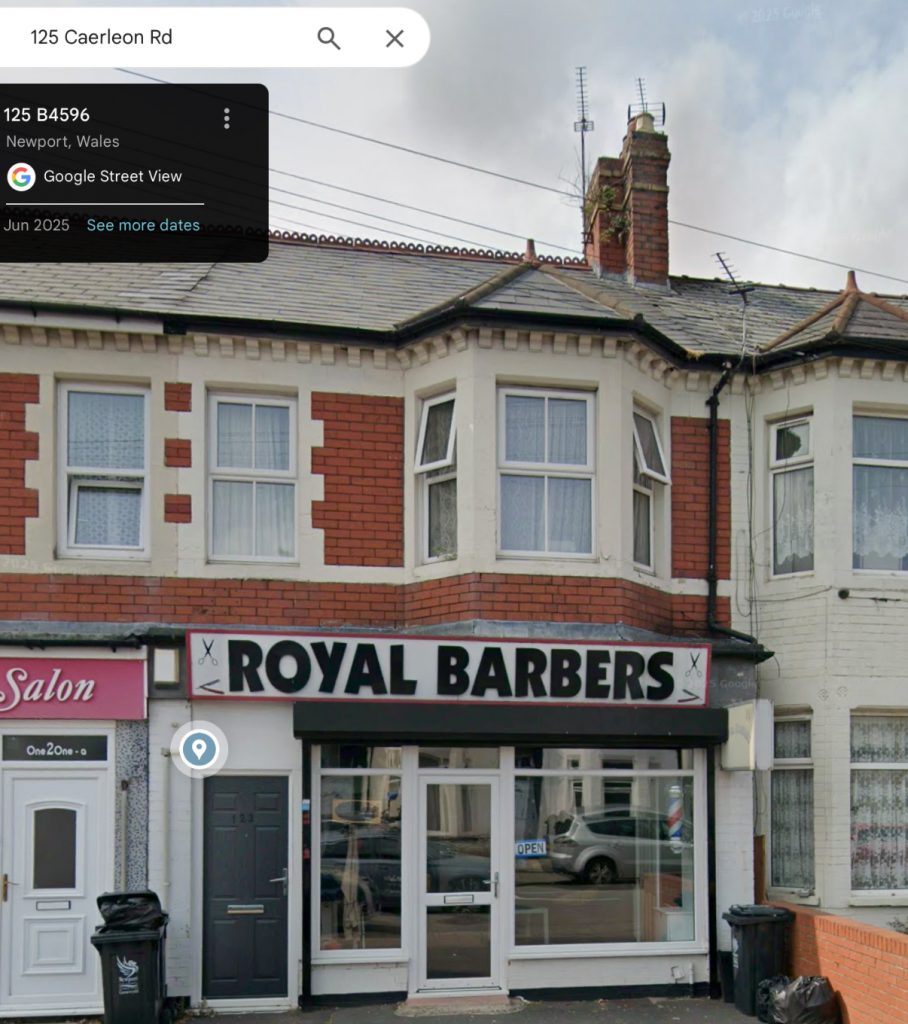

The sudden and mysterious death of Mrs Jenny Morgan of 125 Caerleon Road, Newport caused a sensation in the town in 1923 and was widely covered in the press, locally and nationally. Mrs Morgan was in her mid forties, married to Hubert Morgan, a butcher, with three children, two boys and a girl. The circumstances around her death took some time to clarify and was clouded by conjecture and rumour.

Mrs Morgan died on January 22 aged 45 after a series of illnesses since at least December 9 1922.

During the period she was confined to bed and medical assistance was requested by her family due to vomiting and sickness. Her condition caused doctors some difficulty as they were unclear about the cause of sudden condition and the pain and discomfort suffered by Mrs Morgan. It was suspected by the doctors that her death was due to some form of poisoning probably arsenic.

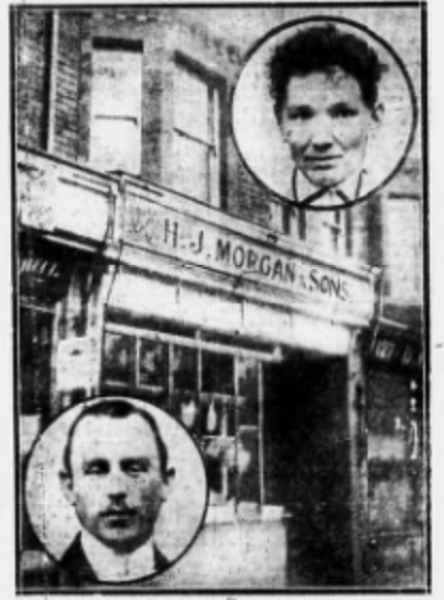

A doctor who lived nearby, Dr Alfred Arthur, stated no such toxins were present in medication he had prescribed for her. When interviewed by the Daily Chronicle in their butcher’s shop at 125 Caerleon Road her husband stated “I do not know where she got the arsenic from. We have heard nothing and know nothing.” Dr Arthur presumed gastritis but shortly afterwards numbness and paralysis set in.

On her death a medical certificate was refused on the basis there would need be a coroner’s inquest into the circumstances of her death.

THE INVESTIGATION

The coroner, Mr Lyndon Moore, said he would seek to find out ‘whether this woman died from some obscure disease.’ He adjourned the inquest and appointed Dr Rudd Thompson to carry out the medical analysis and post mortem. In parallel a police investigation got under way. As it was a suspected poisoning and given the complexity the Chief Constable of Newport Police, Captain Greer, called in two Scotland Yard detectives, Nichols and Ryan. Their efforts proved largely inconclusive.

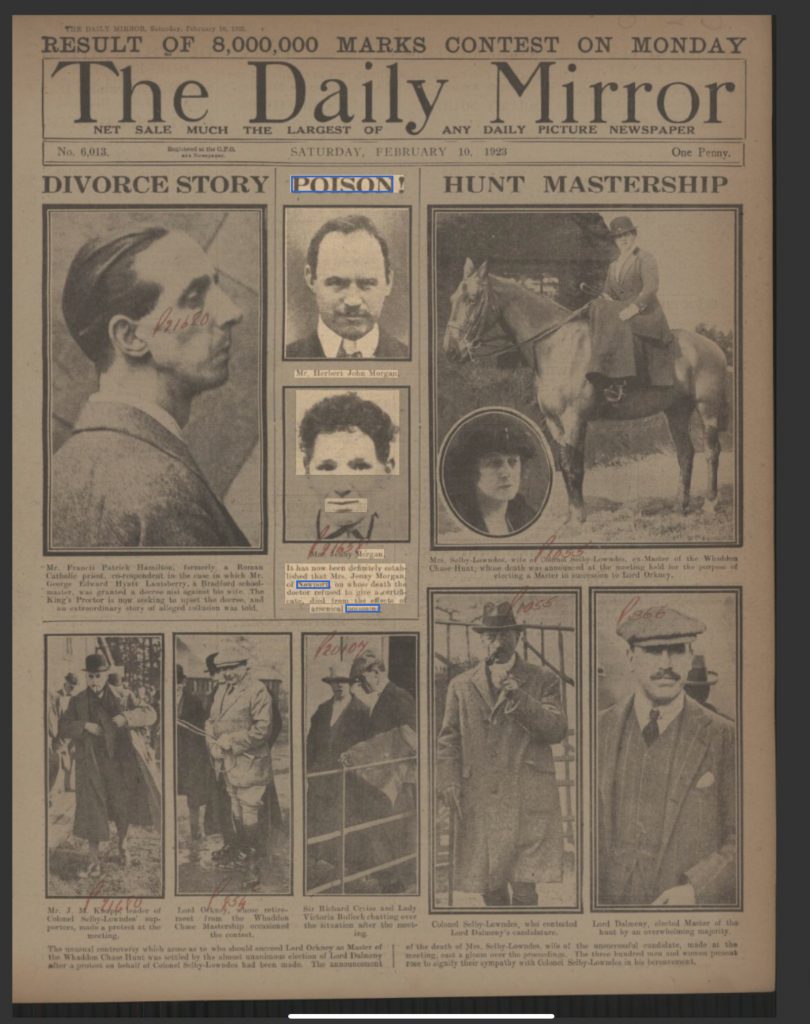

The initial tests showed arsenic present in her vital organs. When interviewed by the Daily Chronicle in their butcher’s shop at 125 Caerleon Road her husband stated “I do not know where she got the arsenic from. We have heard nothing and know nothing.” In fact the London newspapers were all over the story, covering every twist and turn. The Daily Mirror carried it as a front page story on February 16 1922.

THE HEARING

After a number of delays the inquest reconvened on February 27. Twenty witnesses including Mr Morgan, his sons William and Cyril, her sister in law Mrs Webb and Mrs Carthy her niece. The latter cared for her prior to her death. One of the witnesses, a ‘daily help’ named Lucy Jane Beaumont stated that Mrs Morgan fell ill after a trip to London in November. She stated that although she cooked for the wider family only a select few prepared food for Mrs Morgan – including Mr Morgan. Sensationally one of the witnesses called to appear, another servant girl called Edith Andrews disappeared following receipt of a summons to court. She fell into a panic and her body was discovered by her boyfriend in a nearby canal on March 16.

The inquiry itself lasted for eight days, held in the Council Chamber of the Town Hall and Reynolds’s News describes it as remarkable for the number of times testimony was added to by the witnesses concerned. It caught the public’s imagination with a packed public gallery every day and ‘rough postings’ of daily developments pasted on shop windows in the hope of increasing customer.

It was reported that, before her death, Jenny Morgan complained that everything her husband gave her to eat caused a burning sensation in her mouth. Evidence was also heard that her husband had confided to his sister that he was being treated “like a dog” at home. She testified that he had also told her Jenny Morgan was “leading him a hell of a life,” that she wanted a separation, and that he was obliged to pay her £6 5s a week in addition to her rent. She added that he complained he had “slaved and toiled all his life, and this was his reward—that they were going to turn him out.”i

When asked by the Coroner whether he had any suspicion that Jenny Morgan might have died by foul play, he replied, “No.” Questioned further as to whether he was entirely ignorant of how she came to take the arsenic, he answered, “Not to my knowledge.” The Coroner pressed him again: “You are entirely ignorant?” to which Jenny Morgan’s husband responded, “Yes.”

He stated that Jenny Morgan had never refused food from him. When asked if he considered his business more important than his wife on the morning of her death, he replied, “Well, I could do no good by staying.”

A site called unsolvedmurders.co.uk notes evidence given by Mrs Webb “She said that on the Saturday before Jenny Morgan died that a woman showed her a gold wrist-watch and said, ‘He is very fond of me, and gave me this watch’, referring to Jenny Morgan’s husband. When she was asked why she had not given that evidence earlier, Jenny Morgan’s sister-in-law said, ‘I would much rather not have said this. Until I heard the analyst’s report, I thought my sister had died from natural causes. Having heard that report, I thought it was my duty to say all I knew’. The implication is that the woman involved here is Edith Andrews, the young woman who took her own life on receipt of a court summons.

In her final days it was noted by a number of witnesses that Jenny Morgan was assisted by her two sons in the writing of her will.

Critically, evidence had emerged that the eldest son Willie, as he was known, worked in an office run by Shell where weed killer was used to ensure oil tanks were not affected by weeds. As he had access to the weed killer it was felt he could have brought some home. Although there was no evidence to support this. The storekeeper of the Shell-Mex Petrol Company at Newport, where he was employed, testified that weedkiller had been kept in the office since the previous summer, with supplies replaced as they were used. He stated that the tins were accessible to anyone in the office. The weedkiller contained 76% pure arsenic—about 330 grains per ounce—while it was noted that as little as two grains constituted an average fatal dose.

The analyst who examined Jenny Morgan’s body explained: “Weedkiller tastes salty and has a hot, burning taste. I have tested it on my finger, and I have also mixed it with malted milk.”

THE CORONER’S ASSESSMENT

On Friday 9 March 1923, the Coroner delivered his summing up following the testimony of Jenny Morgan’s husband. He observed that only three people in the household could have placed poison in Jenny Morgan’s food: her husband and her two sons.

The Coroner described Jenny Morgan’s husband as a paradoxical figure—at times callous and indifferent, at other times affectionate, loving, and protective—before noting that he had no apparent means of obtaining the poison.

Turning to the son who stood accused, the Coroner remarked that his explanations were “extraordinary” and might or might not be true. By contrast, he found little contradiction between the testimony of the other son and that of the other witnesses.

The Coroner highlighted that the salty taste in the malted milk was consistent with weedkiller and questioned who had access to it. He also considered whether the accused son had told his father of Jenny Morgan’s complaint about the salty flavour, answering his own question: “Not a word.”

During the summing up, a woman witness was recalled. She stated that while staying at Jenny Morgan’s home between 28 October 1922 and 2 January 1923, she had heard the accused son declare that, should anything happen to his mother, there ought to be an inquest. After Jenny Morgan’s death, she added, he urged that he be reminded not to hold on to his bitterness against his father.

The newspaper stated “On March 9 there was a scene that will forever live in the minds of those present. Late that night with the council chamber packed to its utmost capacity with a fashionable audience of men and women the jury returned their verdict of wilful murder against William..Morgan”

A FAULTY PROSECUTION CASE

Willie Morgan had been interviewed without caution but was arrested immediately and remained in custody. He was taken to Cardiff jail to await further charges concerning his role in the death of his mother. At the police court the magistrates found there was insufficient evidence to justify going to a full trial. Subsequently, the Crown Prosecution Service applied to the Courts to remove the case. Morgan was released from jail following acceptance from Mr Justice Roche. His release date was April 27. He was formally discharged in June.

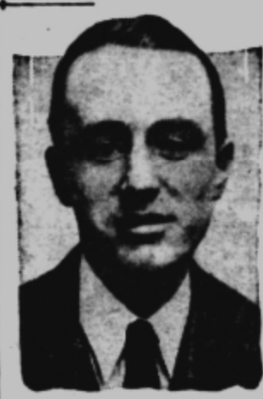

He left the jail and took the journey back to Newport via the train with his solicitor FH Dauncey (of Newport rugby fame). He was reunited with his dad and the rest of his family in a touching scene. The Reynolds News took time out with Willie Morgan to talk about his detention and the behaviour of the courts. He was very respectful given his incarceration. It’s impossible to believe today’s critics of the justice system would be so philosophical or measured.

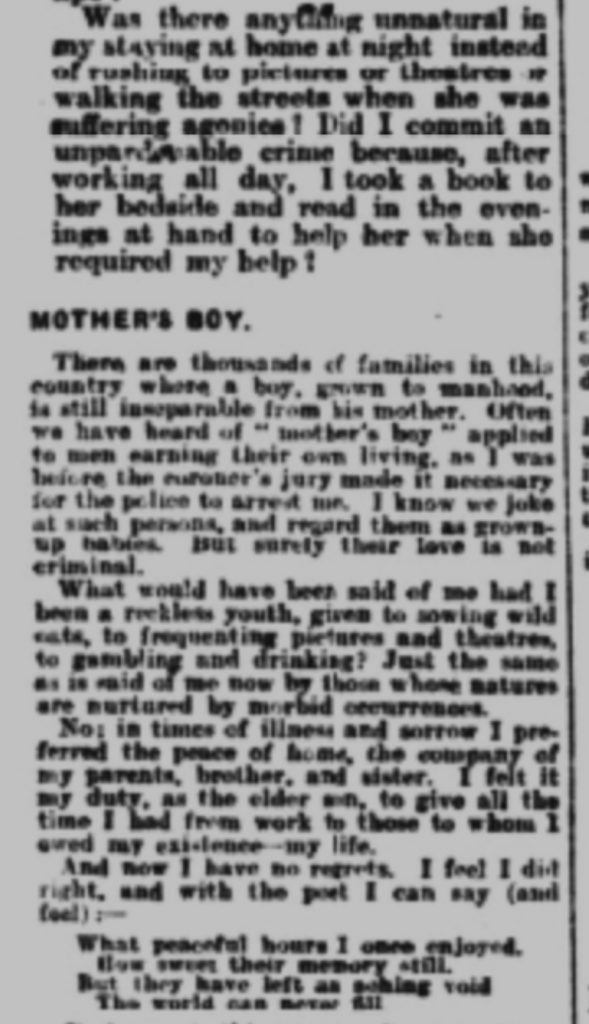

The media focus allowed Willie Morgan to explain his side of the story. In a long newspaper interview after his release he talked about being inseparable from his mother.

See below a cut from the interview about his close relationship with his mum….

The aftermath for the Morgan family

Although the butchers shop was still there it had gone by 1934 but the family remained in the local area.

The youngest son Cyril, a GWR railway clerk married Maude E Joliffe in Oct – Dec 1928 in Ross-on-Wye and she moved to 32 Cornwall Road, St Julian’s.

In 1933 according to the Newport electoral register the family resided at 32 Cornwall Rd St Julian’s (Cyril, Maud – his wife, Hubert and Ann Carthy)

By 1935 Cyril and Maud had moved to 10 Marsh Road in Bulwark. Cyril died 7 August 1973.

According to the wartime 1939 register – Hubert was still at 32 Cornwall Rd , the other occupier was Darcy Dart – an immigration officer. Hubert died in 1948. In 1946 and 1950 Alice Carthy is recorded as the main resident here. It is evident Mr Morgan and his niece were close.

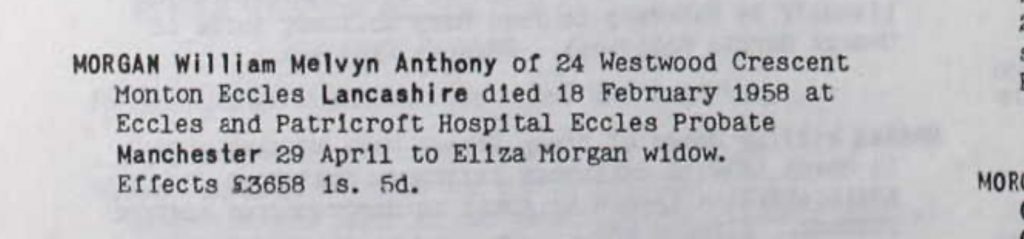

As for William he met and married to Eliza Watkin in Eccles in October 1925. He moved to Lancashire, did he leave Newport to escape the glare of publicity and the impact of his case? He died aged just 58 in February 1958 leaving his wife Eliza an estate of £3658.